Dust storms highlight Iraqi leadership failures as climate crisis worsens

Iraq's most vulnerable citizens are the hardest hit by dust storms, which are growing in frequency and intensity due to both global climate change and government inaction.

BZEBEZ DISPLACEMENT CAMP, ANBAR PROVINCE - Lying in his grandmother’s arms, an 18-month-old named Daher Bilal Kareem writhes in the fierce, dusty heat that permeates his canvas tent home.

The toddler has brain damage and needs special medical attention. When a dust storm hits, his family rushes to keep him breathing.

“He coughs and suffocates from the dust,” said his grandmother, 60-year-old Kafiya Labbatch Abboud, describing the last dust storm that hit their makeshift home in the Bzebez camp for internally displaced people, in the craggy desert of Anbar province.

“I had to take him to a hospital and have them put a spray up his nose – all of this because of the dust. These storms have affected all the families.”

While they are among the hardest hit, the people in the Anbar camps are just some of the millions who have suffered from punishing dust storms that have consumed Iraq with unprecedented severity and frequency in recent months.

Almost no part of the country has been spared. Iraq had 12 dust storms between January and May this year, according to figures provided by its meteorological and seismology commission, part of the Transportation Ministry. The storms have descended upon the valleys and mountains of the northern Kurdistan region all the way down to the south in the Basra Gulf, where they temporarily interrupted trade at Umm Qasr port in May.

When the storms hit, high winds sweep clouds of dust from desert plains into city centers, causing buildings to clatter and bang like machine gun fire. Air travel grinds to a halt as the skies turn an opaque orange, and dusk appears to arrive before noon. Normally bustling shopping streets fall quiet, as people shelter at home. Those who have difficulty breathing are forced by the thousands into hospitals of Iraq’s overstretched healthcare system.

Over a period of two months, Iraq Oil Report interviewed 50 Iraqi government officials, climate forecasters, agriculture sector workers and oil field engineers across eight provinces, as well as residents of some of the areas worst affected by dust storms. Their testimony highlights both global and national factors that contribute to the problem, as well the impact that is most acutely suffered by Iraq's most vulnerable citizens.

“I consider the dust storms as climate extremism,” said Iraq’s Environment Minister Jassim Abdul Aziz al-Falahi in an interview at his Baghdad office. “The country is now in the realm of climate extremities.”

Causes

Iraq's weather patterns have historically been shaped by two winds – the “sharqi,” a south and south-easterly wind in spring and autumn, and the “shamal,” from the north-west in summer. Both have long provoked sandstorms that engulf Iraq and its neighbours. But this year, the high winds have combined with the effects of rising global temperatures, drought, deforestation, and desertification to create a punishing perfect storm.

“It’s an abnormal increase,” said Ali Mohsin Hashim, director-general of Iraq’s meteorological and seismology commission. Although no official was able to provide complete data for previous years, partial figures from the meteorological commission showed a sharp rise in dust storms in 2022 compared to the previous five years.

Every expert interviewed for this article said the crisis conditions were unprecedented, with the dust storms both resulting from and aggravating the effects of climate change in Iraq. Yet the unprecedented crisis is no surprise: even though scientists have been warning about the increasing intensity of dust storms since at least 2013, the government has not taken action to mitigate the problem.

Agricultural land is being cleared and sold off for housing, reducing the vegetation cover and plant roots that bind soil and make it harder for high winds to carry dust particles, according to multiple officials in Baghdad and southern Iraq.

“Now, if I have an orchard or agricultural land, I have cleared it and distributed the land for housing for people,” said Hashim. “There are very large expanses of agricultural land – we can call them part of the green belt, the vegetation cover – where some parties have started to remove the greenery. It’s going to become a fragile, dry area without any planting.”

Iraq has seen consistent decline in vegetation cover over the past 15 years, said Rawiya M. Mahmood, director-general of the Agriculture Ministry’s forestry and combatting desertification directorate.

“If we compare 2006 with 2016, there is a large difference,” she said in an interview in a run-down Agriculture Ministry building out beyond the Abu Ghraib prison, west of Baghdad. “And if we compare 2016 with 2022, we can see a great loss in vegetarian cover, as a result of uncontrolled livestock grazing and the violations which many have committed, taking advantage of the unstable situation in Iraq.”

More than half of Iraqi territory is threatened by desertification, according to

Dhia al-Mashadani, director of environment and climate change at the forestry and combatting desertification directorate. Some 15 percent of formerly arable land has already become completely unproductive because of desertification, he said, while 55 percent is at risk.

Four climate and agriculture officials in Dhi Qar and Basra said rainfall levels have been significantly less than expected over the past two years, leaving land bone-dry and prone to erosion by high winds. Upstream damming by Turkey and Iran has also led to reduced water levels on the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

“The amount of rain in Nassiriya for the 2021 to 2022 season was almost negligible – 32 millimeters,” said Dhi Qar’s meteorology director, Ali Tariq. “That’s compared with the previous season, 2020 to 2021, when the amount was 100 millimeters, and the one before, 2019 to 2020, was 120 millimeters.”

Lower rainfall increases the likelihood of dust storms for two reasons, according to Mashadani.

“The first reason is that [rain] helps the spread of vegetarian coverage,” he said. "But even if land doesn't contain any wild seeds, then it leads to the formation of a crust layer, which prevents winds from carrying dust. When there is no rain, the soil would be dry and loose, and the wind can carry the dust.”

While sand particles are larger, and tend to cause only localized sandstorms because they don’t travel far, the particles of clay and silt that form dust storms can reach Iraq from as far away as north Africa.

Several experts and government officials said there is a correlation between climate change and more dust storms in Iraq.

“The climatic changes that the world is witnessing now have made these conditions even worse, and temperatures have increased, and more evaporation is taking place,” said Dr. Shukri al-Hassan, an instructor at the University of Basra’s geography department. “Now, due to the increase in the dryness of the land and a lack of rain, the soil has become more fragile and disintegrated, especially the deserts of the western region of Iraq and the deserts of Syria and Jordan.”

Land clearing is making Iraq more vulnerable to dust storms, and is happening in the first place because of chronic drought, several officials said. A severe lack of water is causing farmers to abandon agriculture and head to towns and cities in search of more profitable work. Housing projects are expanding to accommodate Iraq’s burgeoning population, replacing the sort of green cover that helps to prevent dust storms.

It is the “transformation of most farmers into businessmen,” that is to blame for the loss of vegetation, said an agriculture directorate official in Anbar.

Many of the pieces of land were originally leased from the state for between 20 to 40 years, he said, but have now been sold off as housing development plots.

“Farmers have begun to cut away their farm lands and sell them as lands for housing, under agricultural contracts,” the official said. “Lands were cleared, plants and trees were reduced, which created a suitable source for these dust storms, which have reached high and unprecedented levels.”

Effects

In the life they had before the Bzebez displacement camp, the family of 18-month-old Daher Bilal Kareem lived near Jurf al-Sakhr, south of Baghdad, and once farmed its lush soil, rearing livestock for meat and dairy products.

But they have not been able to return to their homes for more than half a decade, after the Islamic State (IS) militant group temporarily seized much of Anbar province. Instead, they are among the thousands of internally displaced people in Bzebez and the nearby Ameriyat al-Fallujah camps. They live in dust-caked, ripped tents, with schooling and basic medical facilities provided by a few aid organisations.

While they are among Iraq’s most vulnerable people, they are among the worst-prepared to cope with the dust storms.

“Climate change serves as a threat multiplier for the many other vulnerabilities that households in informal settlements face, particularly without the resources to address concerns or move elsewhere,” said Caroline Zullo, Iraq policy and advocacy adviser at the Norwegian Refugee Council.

One of the most direct challenges posed by dust storms is the health threat.

“In every dust storm in Dhi Qar, there are about 1,000 cases of breathing difficulties,” said Dhi Qar health directorate chief Jaafar Naser al-Aboudi. “Certainly, dust storms have caused an increase in the number of patients in emergency wards, as well as depleting resources, medicines and supplies in emergency situations.”

The economic impact is also significant. With visibility reduced to tens of metres, flights have been grounded at Erbil, Baghdad, and Basra airports. Meanwhile, schools, universities and government offices are shuttered, interrupting students’ education and causing more delays in the already inefficient bureaucracy of Iraq’s public sector.

In the oil sector, while dust storms have not directly affected crude production, multiple energy sector officials said they have halted work such as welding, prevented personnel from accessing sites, and damaged machinery.

“For the first time, field development operations in Dhi Qar stopped due to dust storms this year,” said a senior engineer at the state-run Dhi Qar Oil Company. “That’s unlike previous years, where the development work was not affected or stopped, because there weren’t such severe dust storms.”

A Basra Gas Company engineer said that the dust storms caused production to drop by a quarter at some gas separation units, and impacted the compressors’ turbine filters.

Dust storms have also contributed to disruptions in crude loading at export terminals in the Basra Gulf, where Iraq's primary export arteries have recently been pumping over 3.3 million barrels per day (bpd). In May, a 90,000 bpd decline in federal exports was largely caused by dust storms in Basra that reduced visibility and slowed tanker loading from southern export outlets.

More frequent dust storms also complicate Iraq’s aspirations – as yet unrealized – to dramatically increase electricity produced from solar power.

Dust and pollution are “honestly one of the real problems” for solar panels, said Abdulbaqi K. Ali, an Oil Ministry consultant for energy affairs, in an interview with Iraq Oil Report. “But it remains that the running cost for solar projects – even the cleaning cost – with all that, what we call the levelized cost of electricity for solar, remained less than $20 per MWh, including the regular cleaning process.”

Iraq’s important agricultural sector also bears the brunt of the dust storms. Not only does a reduction in agricultural land cause more duststorms, In a vicious cycle, agriculture – a sector that accounts for a fifth of all available jobs in Iraq, according to a UN report – is badly affected by the weather events.

“You have negative impact on soil and water quality; you have damages directly on plants, even sometimes exposing their roots; and sometimes you have seeds and seedlings that also buried by the sand," said Dr. Salah El Hajj Hassan, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization representative in Iraq.

“You also have damage to agricultural equipment, and the overall health and performance of livestock is affected – they can suffocate in the event of extreme storms. And irrigation canals and pipelines are disrupted, and the growth and quality of dates, grapes and other fruits are affected.”

Iraq’s Planning Ministry said it did not have any statistics on the economic impact of this year’s dust storms. The World Bank was unable to provide Iraq specific-figures, but a 2019 report from the group said that the phenomenon costs the Middle East and North Africa region $13 billion in lost gross domestic product every year — a statistic that likely understates the impact in 2022, when storms across the region have been much worse.

Government paralysis

Iraq has an unsuccessful track record of trying to mitigate the effects of dust storms, and without better coordination between authorities and sufficient financing, they could fail again – or never get off the ground.

Jasib Al-Hajjaj, deputy governor of Missan province, said that two green belt projects in 2012 and 2014 were mothballed because there was not enough budget. The projects would have involved planting trees and other vegetation across a swath of territory to improve soil and air quality, and minimize the risk of desertification.

“The financial crisis prevented the completion of the two projects,” Hajjaj said.

Absent or erratic funding is a major issue in Iraq, where more than 90 percent of government revenue comes from crude oil sales. That makes funds vulnerable to unpredictable global oil market dynamics: like other projects, the Missan green belts fell victim to the prolonged downturn in oil prices that began in 2014.

Right now, the lack of a 2022 budget is seriously harming the government's ability to tackle dust storms, several senior officials said. After parliamentary elections in October last year, Iraq’s political parties have been unable to form a government, leaving key issues such as passing an annual spending plan in limbo.

“The political blockade and postponing the national budget are really affecting the government in all sectors, despite the serious challenges that we are facing,” said Falahi, Iraq's environment minister, citing green belts as specific projects that cannot move forward because of the absent funding.

Even when there is funding and political will, and initiatives get off the ground – authorities in Mosul, Dhi Qar and Kirkuk said they were planning new green belts – a lack of sustained follow-up and cooperation between central and local governments can lead to their failure, officials said.

“The problem isn't in planting trees, or the green belt itself,” said Rawiya M. Mahmood, of the forestry and combatting desertification directorate. “It is easy to build barriers. The question is, who will provide water allocations for these trees? There should be close coordination with the Ministry of Water Resources.”

Looking after trees long-term is the responsibility of Iraq’s governorate councils – which were dissolved in 2019 – and municipalities, she said, describing a lack of follow-up even for afforestation campaigns much promoted on authorities’ social media channels.

“Where are these trees? They perish, because no authority takes on the responsibility for tending to them in the long-term,” she said.

An official in Dhi Qar said that some of 2,000 seedlings recently planted to form a green belt near Nassiriya oil field had died because they were irrigated using salt water. And others believe that, despite the crippling effects of climate change across Iraq, tackling them just isn’t a priority for political leaders who wield enough power to set the government's priorities and agenda.

“We as the ministry, represented by the meteorological commission, have done this detailed report on the storms, and the issues that lead to them, and the solutions,” said Ali Mohsin Hashim.

“So the relevant authorities… do they read the report? Do they take action directly?” Mohsin asked rhetorically, with a slight sigh of exasperation.

Climate geopolitics

Government leaders are quick to point out that dust storms cross borders, and that they cannot be combatted without international cooperation.

That is difficult when Iraq has often strained relationships with its neighbours, including Saudi Arabia and Syria – from where some dust storms enter Iraq – plus Turkey and Iran, which are upstream of Iraq's main rivers.

After a particularly harsh storm hit Iran in May, the Foreign Ministers of Iraq, Iran, Syria and Kuwait held a joint telephone call to discuss dust, and officials in Tehran called for more international cooperation on the issue, including with Iraq. President Raesi of Iran even raised the issue with Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa Kadhimi in May, according to Iran's state-affiliated Tasnim news agency.

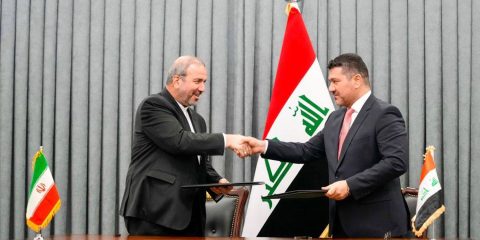

Ali Salajegheh, head of Iran’s state environment organisation, visited Baghdad in May, and in July signed an initial memorandum of understanding over managing dust storms with Iraq’s environment minister in Tehran.

Iran has previously used petroleum-based mulch to stabilise dusty soil, and is now moving to using more environmentally-friendly approaches, Iran’s environment organization said in a statement. It is not clear if Iraq will also adopt the technology.

“The establishment of a financial fund to support environmental plans and projects at the regional level was the main focus of the final statement of the regional meeting of environment ministers,” the statement quoted Salajegheh as saying, without providing details. His office did not reply to a request for comment.

Even without detailed plans on combatting dust storms, the phenomenon has become a geopolitical issue frequently discussed between senior officials, weighing on top of others, such as trade, transboundary water rights, and security.

Dr. Shukri al-Hassan, the Basra University academic, said he expects worsening water shortages to exacerbate the dust storms, with serious repercussions for Iraq’s public health, economy, agriculture, and transport networks.

When it comes to solutions, “we are very late, and we didn’t work on the issue until we found ourselves deep in the problem,” he said. Hassan is also pessimistic the government will take action because the crisis is likely to pass temporarily after summertime. “When the weather changes, from summer to winter, the issue is forgotten. And then it returns more severely.”

Back in Anbar, the displaced families living in tents are coping with the dust storms as another dimension of a cruel reality.

“Nobody is taking care of us at all, not the government — even the [aid] organizations left us and don’t take care of us,” said Kafiya. “There is no aid, no food, no water, nobody cares about us. When it's dusty, it's the end of us.”

Lizzie Porter reported from Anbar and Baghdad. Jamal Naji reported from Anbar. Jassim al-Jabiri and Ali al-Aqily reported from Basra. Jewdat al-Sai'di reported from Amara. Araz Mohammed reported from Kalar. Mohammed Hussein reported from Sulaymaniya. Iraqi staff reporting from Kirkuk and Nassiriya are anonymous for their security.